The Key Report

The Key Report

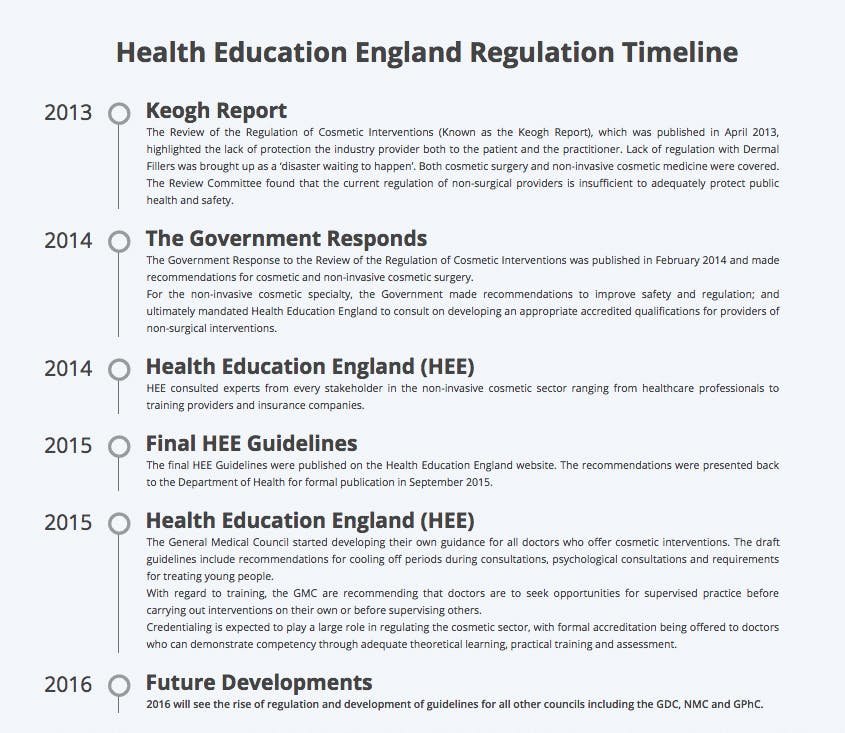

Sir Bruce Keogh reviewed both the surgical and non-surgical cosmetic sector in 2013, in response to the Poly Implant Prothèse (PIP) breast implant ‘scandal’. The French product used industrial rather than medical-grade silicone, and the devices spontaneously ruptured in-situ. Over 45,000 women had received the PIP implant in the UK.

Review of the Regulation of Cosmetic Interventions (April 2013)

- 75% of the market share is ascribed to non-surgical intervention

- Dermal fillers were labelled as a ‘crisis waiting to happen’

- There is no regulation of the non-surgical cosmetic sector

The Keogh Report

- There should be a register of all practitioners who perform cosmetic procedures

- Dermal fillers should be classified as a prescription-only medication

- All practitioners must be properly qualified

- All non-surgical procedures must be performed under the supervision of a clinical professional who is able to prescribe, administer and supervise cosmetic procedures

- Financial offers should be banned, and there needs to be a mandatory code of conduct for advertising

This is not the first time there has been a review of cosmetic interventions – for example, there was also the ‘European Committee for Standardization’ (CEN) review in 2015. CEN is recognised by the EU as being responsible for developing and defining standards at European level. The CEN review, titled ‘Aesthetic surgery and aesthetic non-surgical medical services’, decided to conduct a dedicated non-surgical review – which was ultimately postponed.

In Scotland, the Healthcare Improvement Scotland (HIS) programme supports Scottish Government priorities. From April 2016, independent clinics in Scotland were regulated by HIS – this was instigated by the Chief Medical Officer in Scotland. This includes medical practitioners, dental practitioners, registered nurses, registered midwives or dental care professionals. Independent clinics must register with HIS – application is a non-refundable £1,990 (Regulation of independent clinics, HIS, 2016).

Beauty therapists carrying out treatments in Scotland are not required to register with HIS, and as of yet, there is no regulation preventing them from treating patients. Although the regulators allude to the second phase of change.

Voluntary Bodies: Important or Impotent?

Given the unregulated state of the sector, various voluntary bodies have arisen in order to create some order. Although due to lack of a government-mandated watchdog, these bodies have been criticised as ineffective due their voluntary nature; essentially burdening the compliant whilst the fringe continues to operate in an unprofessional manner. Previously these included ‘Treatments You Can Trust’ (TYCT) and ‘SaveFace’. TYCT won a recent tender to merge their members with the newly formed Joint Council of Cosmetic Practitioners (JCCP).

There are also professional associations which provide services to the healthcare professionals within the sector – but again struggle to protect the public as there is no legislation. Two of these include the British College of Aesthetic Medicine (BCAM), the British Association of Cosmetic Nurses (BACN).

The Health Education England (HEE) guidelines followed on from the Keogh Report, which outlined qualification requirements for practitioners training in aesthetic medicine. It also outlined the major modalities which were being reviewed:

- Injectables (Botulinum Toxin, Soft Tissue Fillers)

- Skin Rejuvenation

- Laser, IPL and LED treatments

- Hair Restoration Surgery

- Orphan Treatments e.g. Platelet-Rich Plasma and Thread lifting procedure

HEE Guidelines (2013 and 2014) for practitioners

- Each modality under the HEE review is given a qualification requirement

- All practitioners performing injectable treatments are required to study to a postgraduate degree level

- Clinical oversight is required for treatment with cosmetic injectables

HEE Guidelines (2013 and 2014) for training providers

- Training courses must have their own degree awarding powers or be Ofqual-regulated, or work in partnership with such organisations

- A minimum of 50% of the curriculum must be devoted to the development of practical skills

- Delegates must subsequently pass a rigorous and standardised assessment

- Supervisors must be able to provide clinical oversight and be proficient with the treatment being trained in (a minimum of 3 years experience)

General Medical Council (GMC) guidance for doctors (April 2016)

- Doctors must market their treatments responsibly, including not offering financial incentives for cosmetic procedures

- Doctors must conduct a face-to-face consultation and seek consent themselves without delegation

- Patients should be given a cooling off period in order to make a voluntary and informed choice to proceed with treatment

- Doctors should take particular care when treating young persons

- Doctors should be mindful of the psychological drivers for cosmetic treatments and when these may be pathological

Regulatory Bodies

The Joint Council of Cosmetic Practitioners (JCCP) and Cosmetic Practice Standards Authority (CPSA) were formed to implement the HEE guidelines. The JCCP has three main responsibilities: to oversee training organisations, and to curate a register of qualified practitioners who are displayed on a public-facing register, and to oversee premises standards.

Various associations signed a memorandum of understanding to work together in May 2016: BACN, BCAM, British Association of Dermatologists (BAD), British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons (BAAPS) and British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons (BAPRAS).

The Hair and Beauty Industry Authority (HABIA) was added September 2016.

The public-facing register hopes to drive standards by providing a vetted list of qualified practitioners.

Entry to this register starts at ‘Level 4’, to encompass aesthetic practitioners in the domains of skin rejuvenation and laser treatments. There will be two streams within the register: Those practitioners who are regulated by Professional Statutory Bodies (i.e. the GMC, NMC etc.), and those practitioners who are not. In order to practice Injectables (Toxin and Fillers) at a Level 7 standard, and to enter the register for these treatments, non-medical practitioners must be able to demonstrate that they are practising with clinical oversight and supervision.

CPSA responsibilities

- Reviewing evidence and updating guidelines on existing defined modalities and future emerging modalities

- Setting the standard for clinical and practice proficiency

- Collect adverse event data and developing patient outcome and experience measures

- Working in partnership with the JCCP on standards with regard to aesthetic treatments

There has been a heated debate amongst healthcare professionals who believe that non-medical practitioners have no place in carrying out fundamentally medical treatments. Unlike domains such as surgery or veterinary medicine, non-surgical cosmetic treatments are not protected by law and at present, it is not illegal to insert a needle into another person in the UK. If these guidelines aren’t legally enforceable, the question is: what is the point in engaging with them?

Arguments against the new guidelines

- This is again only regulating those who already have accountability

- The public need to be aware of these changes so that they seek out practitioners who adhere to the new guidelines. Where is this funding going to come from?

- There is scepticism amongst the sector because there have been promises of regulation for many years, with no tangible improvement

- These guidelines ‘legitimise’ non-medical practitioners carrying out injectable procedures

Arguments for the new guidelines

- This is the first time there have been defined qualification requirements. Healthcare professionals aspire towards best practice, and these new guidelines will drive up standards nationwide

- Implementing a form of regulation with data collection will help to drive better standards and safe experimentation with novel therapies in a sector with an unclear but rapidly developing horizon

- Regulation is a cornerstone of academia and research, which will support further growth of the sector

- These guidelines lay the foundation for statuary regulation

The Raging Debate

The involvement of non-medics in non-surgical aesthetic practice is the most contentious issue of all. By virtue of the sector is unregulated, there is inadequate data to present to the Department of Health to suggest that certain groups pose a risk to patient safety. In an unregulated sector, insurance companies can be seen as a regulator by proxy. But this poses little reassurance in a capitalist economy where profits are the raison d’être for insurance companies. This is not helped by the fact that there is no mandatory collection of data which might help in some insurance companies choosing to insure only low-risk practitioners. To see how the UK is faring, parallels can be drawn with other countries. In France, for example, only plastic surgeons, dermatologists, ENT surgeons and maxillofacial surgeons are authorised to treat patients with cosmetic injectables to the face. In North America, regulation varies in each state, but the majority of states have some form of state-governed regulation preventing those without appropriate qualifications from treating patients.

“A separate dilemma revolves around complication management of other practitioner’s patients.”

In the absence of strict laws and availability of data, industry marketing has a significant influence on aesthetics. Companies take advantage of this influence to drive significant profits. Resistance from beauty therapists is unsurprising. Those non-medics who have had 10+ year careers in providing non-surgical cosmetic interventions are starkly determined to maintain their role in the sector and aggressively oppose the notion that they are not qualified to provide cosmetic treatments. They are doing nothing illegal, after all… The argument of healthcare professionals is ultimately around accountability, their professional code of conduct, and the ability to provide clinical oversight and prescribe. Accountability, in particular, is ubiquitous in other areas of clinical practice, and without mandatory legally enforceable regulation by the Department of Health, the Keogh Report, HEE and JCCP appear to miss the mark in providing this cornerstone of protecting the public.

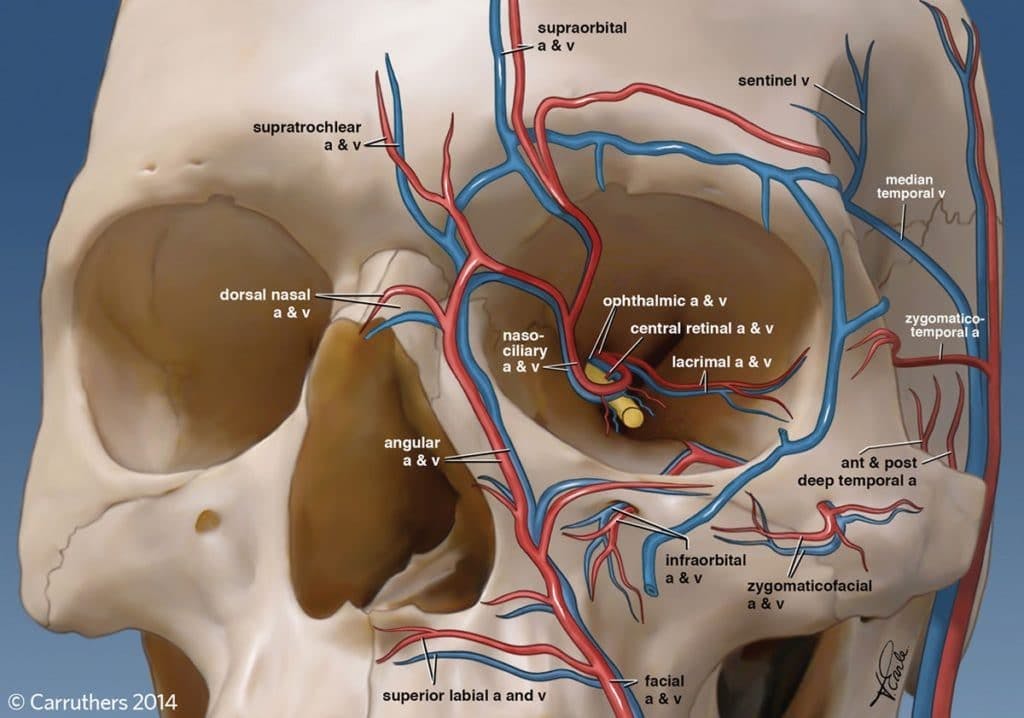

A separate dilemma revolves around complication management of other practitioner’s patients. Those practising without accountability and a network of peers or clinical oversight are unquestionably endangering the public. Furthermore, to what degree should the NHS support complications which arise from the private sector? Chelsea & Westminster Hospital in London spent £43,000 over a 15 month period managing complications from the private non-surgical cosmetic sector. The NHS does not routinely attempt to recover costs from private practitioners.

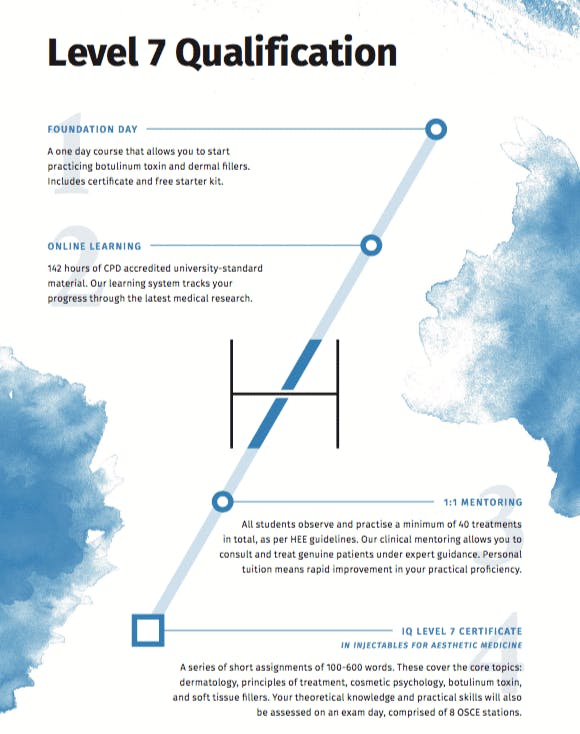

Educating the public is critical to creating a better sector for all involved. 2018 may see a heightened interest from mainstream media in non-surgical cosmetic treatments, which may help to highlight the current disparity in standards. New guidelines to require a Level 7 qualification in injectables has certainly achieved some good. Practitioners entering the speciality are now exposed to a much higher standard of training than before. No longer are one-day courses seen as a viable option: supporting this is the GMC guideline which states that doctors should seek ongoing mentoring before entering practice independently.

There has been a proliferation of Level 7 training centres, and particular concern about non-medics training to a postgraduate standard. It is hard to conceive how this is possible, given that an undergraduate foundation is required before embarking on further education. The published Level 7 qualification, through the Ofqual-regulated Awarding Body ‘Industry Qualifications’, outlines the learning outcomes and assessment criteria of the units involved in the qualification.

Total qualification time: 277 hours & 8 Units

- Principles of History, Ethics and Law in Aesthetic Medicine

- Principles of Treatment in Aesthetic Medicine

- Principles of Cosmetic Psychology in Aesthetic Medicine

- Principles of Dermatology in Aesthetic Medicine

- Principles of Botulinum Toxin Use in Aesthetic Medicine

- Practice of Botulinum Toxin Use in Aesthetic Medicine

- Principles of Dermal Filler Use in Aesthetic Medicine

- Practice of Dermal Filler Use in Aesthetic Medicine

Those practitioners without a thorough background in healthcare and the consultation process (alongside inherent ethical values instilled during undergraduate training) may find the Level 7 standard extremely challenging.

“Mammalian drivers for self-improvement, grooming, and beauty are natural.”

The rise of social media

Aesthetic Medicine is one of the fastest growing healthcare sectors in the world. One can speculate that social media is a large driver of this – supported by the fact that at major international conferences, there are educational seminars on ‘how patients can look better in their selfies’. The lack of mandated regulation, alongside a booming sector which inherently attracts more vulnerable patients than other typical wellbeing services, is a major concern.

Mammalian drivers for self-improvement, grooming, and beauty are natural. It is nothing new, Ancient Egyptians had many beauty practices, for example rubbing heavy metal salts on their face to improve their appearance. It just so happens that in 2018, we have minimally-invasive technologies which can provide drastic outcomes, which come with increased risk and cost. These non-surgical interventions should be treated with respect, something which is not happening in the UK.

In such a rapidly growing and changing sector, a form of regulation is essential. Historically, there have been cycles of attempts at regulation. The HEE review is certainly not without criticism, however, it can be seen as England’s first real attempt at governing this embryonic but exploding speciality. It is yet to be seen how the JCCP register will be received, and which stakeholders ultimately benefit and whether patient protection is improved as a result.

The JCCP launches on the 1st March 2018

REFERENCES

- BBC 2013, Q&A: PIP breast implants health scare . London: BBC

- Press Release – New Joint Council for Cosmetic Practitioners (JCCP) 24th February 2017

- State by State Dental Botox Regulations (USA)

- Guidance for all doctors who offer cosmetic interventions, April 2016

- Review of the Regulation of Cosmetic Interventions, April 2013

- What is a Level 7 Qualification? Harley Academy

- HEE Guidelines 2016: A Brief Summary. Harley Academy

- Regulation of independent clinics from April 2016. Healthcare Improvement Scotland.

- New qualifications unveiled to improve the safety of non-surgical cosmetic procedures. Health Education England, 2016.

- European Commission Medical Devices Guidance Document. Medical Devices Guidance Document: Classification of Medical Devices. Guidelines relating to the application of the Council Directive 93/42/EEC on Medical Devices. 2010

- J Collier, R Young, N Kirkpatrick, M Gregori, N Hachach-Haram. Complications of facial fillers: resource implications for NHS hospitals. BMJ Case Reports. 2013.

- Review of the Regulation of Cosmetic Interventions: Summary of the Responses to the Call for Evidence. Department of Health. 2012 (Accessed 17 April 2013)

- IQ Level 7 Certificate in Injectables for Aesthetic Medicine. Industry Qualifications.

All information correct at the time of publication

Download our full prospectus

Browse all our injectables, dermal fillers and cosmetic dermatology courses in one document

By submitting this form, you agree to receive marketing about our products, events, promotions and exclusive content. Consent is not a condition of purchase, and no purchase is necessary. Message frequency varies. View our Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions

Attend our FREE open evening

If you're not sure which course is right for you, let us help

Join us online or in-person at our free open evening to learn more

Our Partners

STAY INFORMED

Sign up to receive industry news, careers advice, special offers and information on Harley Academy courses and services